So I haven’t blogged for a while, who cares eh?

I finally put forward an article to get published. And it has. Is it there to be challenged? Of course, if you feel my work is incorrect, please do – that is what archaeology is all about. You can find it in the latest publication of the Monmouthshire Antiquary. I will put the article up within its entirety after I have explained my latest thoughts.

http://www.monmouthshireantiquarianassociation.org/publications-3/

This blog post has nothing to do with the journal whatsoever. Please do not, on any account, link each one with the other.

Is it a big thing getting published? – No it is not.

If you carry out archaeological research it should be a requisite that you publish – otherwise what is the point?

Am I happy? – No I am not.

The medieval landscape that Llantarnam Abbey created, and developed, for over 300 years is still being destroyed as each development goes by. The latest cock up is as big an archaeological cluster-fuck as you can get. It is to do with the development of the site at the old comprehensive school in Llantarnam.

This is a brutal read; but people have to be accountable for this, currently they are not. This is not a finite resource we are destroying here, there will not always be something to investigate, post development archaeology confuses the issue. The quiet approach of ‘lets make sure this does not happen again’ is fine with a lot of people; but when that is conveyed verbally, it gets forlornly forgotten. And it has, again. People never remember a punch in the face if it never actually happens. Well, take this on the chin and bloody well buckle up – do your jobs properly please. This is getting embarrassing now.

This site is situated on the grange of Ysgubor Cwrt, now re-named as Court Farm. It is a big old grange, the home grange no doubt, with lots of archaeology left within Cwmbrâns developed landscape. It is a pleasure to investigate both in the field and cartographically if you are of the monastic landscape persuasion. It had a farmhouse, barns – hence the name – and a few mills. It straddled a canalised brook and river (The Dowlais and Afon lwyd) which then fed long mill leats, that were probably utilised as canals to deliver grain to the said mills. The leats could also easily have been used as watering channels for cattle and sheep, utilised as fisheries, while providing the necessary fluid for water meadows on a wide scale. After all of that, the water from both systems had been managed and curtailed into the grounds of the outer court of the abbey and by means of a sluice gate, they undoubtedly flushed the latrines of the inner court before being guided back into the lwyd. All handy stuff for the abbey, and something they (Cistercian abbeys) were well accustomed to on a european wide scale.

That being said, you can imagine my excitement when I asked for the archaeological desktop report… I had visions of excavations, community projects, environmental analysis (which would be a first, but lets not forget the developer is paying for this), and all round archaeological investigation. I was excited, and rightly so. It is ripe for archaeological investigation.It offers up an archaeological cherry that an archaeologist should want to bite. But they didn’t. They were blind to the fruit being offered. To them it was an acorn…

The archaeological desktop report is fascinating – because there isn’t one. I am very tempted to copy and paste the replies I received off both the Gwent Glamorgan Archaeological Trust and the planning department at Torfaen County Borough Council. I won’t though, you’ll all think I am making them up. Yeah, things are that bad. It is a sad state of affairs when a landscape medievalist, who relegates his archaeology to hobby level, has to blog because those that are supposed to have knowledge do not do what they are paid for. Various people, within organsiations, are not doing what they are paid to do.

I have received some mind boggling replies to my enquiries on this, ‘There was not a need to compile one as there was no archaeology watching brief carried out while the school was constructed’ The planning officer from TCBC said that she ‘didn’t see the need for one’. It really is outstanding stuff and is top drawer if you like to to pat professional incompetence on its back. You know that first edition Ordnance Survey they carried out? Scrap it, it is obviously worthless.

It is poor, fraudulent, archaeology. It all stems from archaeological identity; how archaeologists view a site.

It is why I wasted thousands of words explaining it. Stop it archaeologists, you have a job to do, one of those is not looking back at the investigative history of a site. Unfortunately, those who have the power to act do not have a comprehensive understanding of a medieval landscape. For shame.

I’m glad I have got through this post by being ultra polite. The article will follow.

History is upon us right now. It is a necessary, but saddening, weight that we all have to bear. The media is pummeling recent historical events, through various types of delivery, at us at an incredible rate. And so they should. Seventy years ago the largest military amphibious invasion in history took place on Normandy beaches that eventually led to the downfall of Hitler’s ill perceived utopia. So why would I blog? What, if anything, has come to light that would make me want to blog about a subject that is already adequately covered by the media? Allow me to explain…

During WWII many gentry and private estates were utilised by the military in this country for various tasks. These were big estates, they offered many boxes that had to be ticked. Isolation was key while providing suitable housing for officers and suitable areas of land for camps for those that volunteered or were conscripted. These estates were the icing on the military cake. It was a win win situation across many sites throughout Britain. Although they are way to many to list, one thing is clear, landowners did their stuff to help the war effort in as many ways as they could. I have no idea if the landowners were paid for this, compensated, received parliamentary privileges, or whatever, that does not interest me one iota. What interests me, as a life long resident of Cwmbrân, is did it affect the landscape that I currently live in?

It did.

Llantarnam Abbey’s estate developed into an American military base. It is a fact that is not extensively published. Local historians have not published the issue although I do not think that is intentional. I think it is more due to the fact that many people do not simply know of what was happening in Cwmbrân at that particular time. That was normal for the Second World War, secrecy was of the highest order. However, would our historical perception of the site change if unpublished details were to be presented into the public domain?

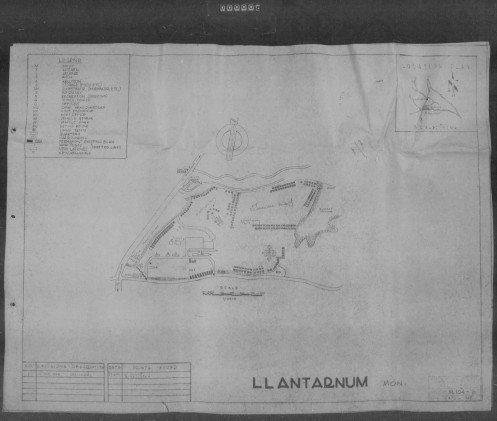

This map outlines the American camp that was within Llantarnams estate in the early part of 1944. I feel inadequate re-producing this quality of cartography. It is the highest resolution I have: it will have to suffice. What does it signify, if anything? Well, quite a lot actually. This map outlines the base camp where thousands of American Soldiers lived before they embarked to Normandy. This camp, this field, is where many of them ‘strapped up’, as they prepared themselves ready for the biggest day of their lives. Many of them would never have returned to Britain, let their homeland.

The site was one of 27 US marshalling camps set up between Chepstow and the Gower in advance of D-day. Llantarnam camp was in existence by 22nd March 1944, was known as camp U74. It housed 2046 troops and 210 vehicles and was a ‘summer tented camp’. The troops came from a range of US regiments. This included infantry, armoured and medical corps who were mustered there prior to their embarkation from Newport to the south coast to prepare, be briefed and waterproof the vehicles, prior to D-Day. The majority of the troops (1374) and 203 of the vehicles left the camp between the 30th May and 3rd June 1944, and were destined to be part of the troops mobilised on D-day -1. The camp in Llantarnam would have contained a large number of buildings, both temporary and more permanent, that would have facilitated the build up of the troops.

So whats my beef?

The site of the camp is destined for development. That is fair enough, things move on, but the initial archaeological assessment mentioned nothing of the above. Cotswold Archaeology were responsible for that report, CADW also never mentioned it. After retorts were sent to the planning office, GGAT thankfully mentioned that the WWII camp had been ‘obviously overlooked’. It is too late now though, the initial reports leave a long lasting imprint on those responsible for planning matters. It is important to remember here that when council officers are advised on these matters, unless evidence is presented to them, they can only make an informed decision based on what has been written in an actual report. Initial reports deliver a heavy punch.

So why was it missed?

I have no idea. The simplest of internet searches can re-produce what I have laid down above, it really is not hard to do. The report by CADW on this particular site was, in my opinion, woefully inadequate. They do know of this camp, WWII sites along with later cold war sites have been recently scheduled. The problem lies within the first report. As it is ‘official’, CADW have an awkward dilemma facing them as to whether they produce a new report overriding the first. As this situation is deemed as ‘awkward’ the easiest thing to do is, erm, nothing. If you are stuck between a rock and a hard place, never move.

Which of course stinks.

There is an upside to this site although I am slightly loath to mention it here. I have been told that unless new evidence presents itself for this particular parcel of land, no new reports will be forthcoming. I have carried out an extensive landscape survey of the field that the American soldiers camped in, my research suggests that there is a strong medieval imprint stamped on the landscape.

Let us all hope that that will be enough for a new decision to be made.

Least us forget.

It has been a long time people, I make no apologies for that. Lots of things have happened here that I shan’t bother you with for a variety of reasons. I am now in my final year of university although I am quite sad at that. It has been fun and the learning curve has been unexplainable, exciting, saddening, hard, but altogether, rewarding. It appears I picked the right course. The only thing I would change would be my first year of study.

So what has prompted my emergence from blogging hibernation? Well, the title sorta gives it away a tad, but before I rip Newport Council a new one over the mural, lets have a little look at the background to this. I feel I am qualified to comment.

Aiming at the Council Chamber – Sorry, at the Chartists

The mural that has been destroyed is commonly depicted as the Newport Chartist Mural. It was more than that as it also illustrates a few other events in Welsh political history. However, just for now, lets go with the Newport uprising and have a little look at the background to that.

In the early nineteenth century, the politics of Monmouthshire was controlled by two country seats in Parliament. The Morgans of Tredegar held the monopoly on one, the Duke of Beaufort held the other. Two towns in Monmouthshire basically controlled who was appointed due to their populace, namely Newport and Usk.

Around 1806, a fella named John Frost returned from London, established himself in Mill Street as a tailor draper and became a radical spokesman for manhood suffrage (sorry ladies, you had to wait for your turn). Frost was determined to break the gentry stranglehold that occupied the Parliamentary seats for the county. To do this he teamed up with Thomas Prothero, who happened to be the Town Clerk for Newport, and the lesser industrialist John Hodder Moggeridge. Launching a series of ferocious broadsides against gentry political corruption and, in turn, his former colleagues, Frost ended up alienating himself to the extant he was gaoled for libel in 1823. Undeterred, Frost established the Political Union of the Working Classes in Newport in 1831.

The Reform Act of 1832 infuriated Frost and his fellow radicals. Fuelled by this disappointment, like minded people joined Frost and Chartism started to gather pace. By 1839 over 400 chartists were active in Newport alone. The leaders of Chartism started lecturing throughout the eastern valley. The lectures diffused outwards from Newport towards Abergavenny. Not widely known is their initial target audience. The large mass of bodies in the coalfields were left well alone (OK, fess up, who split this fact on the Labour run Newport Council?), it was middle class support they were after. This changed when London’s Working Men’s Association appointed a roving ambassador called Henry Vincent. Soon after, 20 new chartist branches were established with the number of active supporters rising to as many as 20,000.

A huge petition to Parliament was beginning to take shape. Vincent held many meetings, heralding that if the petition were to be rejected, ‘every hill and valley of Wales should send forth its army’. Stirring words indeed, and as such it should be no surprise that the authorities, both civil and private, starting putting in place measures to combat the Chartist tsunami. Soldiers entered Abergavenny, Newport and Monmouth. Warrants were issued for the arrest of the Chartist leaders which concluded with Vincent being arrested and thrown in Monmouth gaol. But it was never going to be enough, and it could easily be argued that these actions fanned the Chartist flames. By the night of November third 1839, an army had amassed to ascend on Newport. Frost led from Blackwood, Zephaniah Williams from Ebbw Vale and Nantyglo, while the watchmaker William Jones, led the men from Pontypool. The following day is well documented.

So what is the kerfuffle in regards to this historical background and the last few weeks? In 1978 Kenneth Budd was commissioned to create a mosaic depicting the chartist struggle and subsequent battle. And, he did a jolly good job of it. 200,000 pieces of tiles and glass were painstakingly pieced together to produce what can be considered to be a masterful piece of historical art, it was of extraordinary quality.

The mural lined the walls of a subway leading to John Frost Square in Newport City’s centre. Thousands of people walked past it daily giving them a constant reminder of the struggle of past years. If truth be known, we are currently going through the same struggle in the present day. It should be of no surprise that subsequent London Parliaments continue to protect those at the top; the gentry and industrialists of yesteryear. For me, it was the ultimate historical identity link for the ordinary person to past events. It gave Newport people historical identity. It worked two ways, they went to work or walked to a rugby game based in Newport. Either way, they walked past the mural.

Newport City centre needed to be developed. The rise of Cwmbran’s shopping centre has overseen the demise of both Newport and Pontypool shopping centres in the eastern valley (over and above its original purpose). The subway the mural is housed in was Included in the development area. As such, the mural was under threat. A request to list the mural, to give it some sort of cultural protection, was dismissed by CADW, apparently out of hand. The South Wales Argus (18 September) reports,

” A spokesman for Cadw said the mural, located in a walkway off John Frost Square, had fallen short of its criteria for listing on grounds of its “special architectural interest”.

“The quality of building to which the mosaic is attached is poor and the underpass itself has no intrinsic design merits. It was also felt that there was no specific association between the location of the mural and the Chartist uprising,” he said.Cadw had worked with the council to find a future for the mural but “the costs associated with relocation are too great for this to be a viable option.”It goes on to state,

“The demolition of the mural is not planned to take place as part of the first phase of demolition works at John Frost Square that the council is currently seeking a contractor for.”

What comes next is derived from a statement made on Newport Councils Faceboook page.

“Following the submission of the listing request, we took Cadw’s advice and commissioned Mann Williams Consultants, experts in the field of civil and structural engineering, about the potential for relocating the mural. It was made clear that it would cost at least £600,000 and there were real risks that the mural would not survive such a move. We have to consider the cost to the council taxpayer, especially in the current financial climate.”

OK then, lets take at those statements in greater detail.

- “It has no special architectural interest”

Really? How many other 35 metre long murals do we have in south east Wales depicting the chartist movement?

- “no specific association between the location of the mural and the Chartist uprising”.

Really? Erm, it led to JOHN FROST Square.

- The demolition of the mural is not planned to take place as part of the first phase of demolition works at John Frost Square

Really? That didn’t quite ring true did it?

- “Followed Cadw’s advice and commissioned Mann Williams Consultants, experts in the field of civil and structural engineering.”

Really? And why were specialised conservation and contsruction renovating experts not consulted? Engineers built the second Severn crossing and the Channel Tunnel, I am not sure how many of them have created an artistic master piece made up of glass and ceramic tiles.

- “It was made clear that it would cost at least £600,000 and there were real risks that the mural would not survive such a move.”

This last one is my favourite. Watch this.

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=croLnqK8a2I

Now those little diggers pack one helluva clout. I know this as I have been hit by the swinging arm of one (although I did manage to catch a piece of 14C monastic tile before I hit the ground). You can quite clearly see that the machine is having considerable difficulty demolishing the mural. Not exactly un-survivable if it had been carefully re-located doncha think?

The mural has been laid onto a sand and cement mortar which in turn has been laid onto what is called metal rib lath. The geomatric design of rib lath makes it incredibly strong when rendered with sand and cement, so much so that the mural could have easily been taken down, without major damage, stored for a very long time, and then refitted when necessary. In fact, so big and strong were some of the chunks of the demolished mural, the Police gave some to the protesters that were present on site. That in turn prompted this astonishing Tweet

What on earth are @gwentpolice doing handing out pieces of the Mural!?

Hmm, quite Cllr. Now hang your head in shame for your incompetent ignorance. For shame.

Given the above the mural could easily have not been incorporated into the current development for a fraction of the cost quoted. And I mean a fraction.

In short, Newport County Borough Council have dropped a bollock here, one of monstrous proportions.

And they have form. Where do you think half of the Castle is? Or the Corn Exchange? They don’t even deserve the Newport Ship which, by the way, an independent consultation said would bring millions of pounds into Newports economy over many years.

Strange how they have chose to ignore that isn’t it?

Perhaps not.

I should really be following up the last blog post on Coed-Eva Mill but other things have cropped up, another two development sites in Cwmbran – or should I say Torfaen? I have a lot to follow up on as well, a lot of further information has come to light in regards to the mill in Coed-Eva but until I can get over to our illustrious County Hall, things may have to stay quiet on that front, although not for long.

Many of you may know what interest I have, from a historical perspective, in this area. I have, quite horribly, just realised that my about page on wordpress.com has not been filled out to let people, who do not know me, what I am all about. So here is a very quick summary that will enable you to understand why this next blog post is all about the Welsh institution that was in South East Wales, that of Llantarnam Abbey.

I am currently a part time student at University of Wales Newport – Caerleon campus. I am studying part time, for a MA in Regional History and I am half way through my second year. My final year will be taken up by my dissertation topic. There are many things my dissertation could centre on that would not be associated with Cwmbrans landscape, but there is one subject that has grabbed my attention over some time now, monastic water systems, and it is these that I have been investigating. I think the subject is fascinating, the ability to control a natural resource that wants to remain level at all times.

The ‘working title’ may be something along the lines of ‘The Monastic Hydraulic Systems of Llantarnam Abbey’. I have to say working title, for if I included all of the systems that I have researched, the work would easily surpass the 20,000 word limit that is placed upon me. Lets just say that the hydraulic systems directly associated with Llantarnams inner and outer precincts will be dealt with. These have been touched on in an academic manner before, the Gwent Glamorgan Archaeological Trust have covered part of them while conducting a watching brief for a by-pass road built recently. As with all watching briefs there is a limit to how much of the surrounding landscape you can investigate and so the accompanying report would of course, be quite limited in its scope. The advantage I have is that I have not been constrained by any limits. I am lucky enough to go out and about into the landscape to carry out a thorough investigation. And that is what I have done for the last two and half years, I have been hands on so to speak. The water systems I have investigated associated with the Abbey are immense. It is important, to me at least, that these investigations have been undertaken whilst in the field and not at a desk. The desktop work is important, don’t get me wrong here, but it is only out in the field that you get a real feel for the archaeological remains.

Last week I attended a public consultation that was held by Torfaen planning to have a look at the proposed plans, for housing, at Llantarnam Abbey. Planning permission had already been granted, but that was for an industrial park – we have not enough already apparently! – this consultation was for a change of planning from industrial use to housing.

Please, take a look at the plans.

It is the largest group of buildings to the centre right of the picture that most concerns us most. Personally, I find the size of that development quite shocking. Why we have to build on these green field sites when there are plenty of brown field sites is a bit mind boggling, nevertheless, the permission has been granted. Take a look at the photo I took of what was said about the archaeology.

Now this is exactly my problem with the planners in Torfaen, it has to be said that it is not their fault and you can also add the advisors from GGAT to that list as well. You see, that statement is technically correct; although it should be added that a lot of metal detector finds have been discovered very nearby. According to the Historic Environment Record (HER) there is nothing there, but should we believe it and just write off the possible archaeology with the sweeping statement above? Of course we shouldn’t. For starters, I could easily construct an argument that the majority of that large estate is inside the outer precinct of the medieval abbey. Whether I am right of course is another matter, but I could still build the argument.

Not only that, the much written about medieval deserted villages of Llantarnam may not be all they are made up to be. Some buildings are that close to the current abbey building that another argument, for them being inside the inner precinct, could also be construed. The excavations that produced these conclusions were not published fully, as such, in my opinion, they are open to re-interpretation.

Again, the buildings that are thought to be in the other ‘deserted medieval village‘ nearby, could quite easily be in the outer precinct. If that is the case, who is to say that the proposed land to built on does not hold similar buildings?

The possibilities are endless. Nobody has really looked at the abbey in an in depth manner since the last excavations. It is in Cwmbran remember. It may be thought of as a difficult ‘subject’.

I have mentioned this before. There is nothing of interest in Cwmbran whatsoever, or at at least that is the current popular historical culture that is generated around here; it is not helped by the wording of most planning decisions. Once again the destructive legacy, left to us by Cwmbran Development Corporation, has hit home. But hang on, is this not 2011, soon to be 2012? How long have we been getting rid of stuff in the Cwmbran area due to there being nothing on the HER due to the ineptitude of the Development Corporation? There will be nothing on the HER of note, they did not look. As such, the current planners are hamstrung. It is a viscous archaeological circle we find ourselves in.

So, would you like to see what is in the area proposed for the development? Not a problem but please allow me to quickly explain how the Abbey was fed by the water systems it felt the need to employ.

The are two major sources for the Abbey, that are from outside of the outer precinct, that are popularly thought to have drawn from the Afon Llwyd and the Dowlais Brook. The tapping of the Afon Llwyd was made some distance away on Avondale Road, after the bus station in fact, and carried on down Llantarnam Road, feeding the two mills near Brook House before entering its tail race… I’ll leave that one there as it gets quite complicated after that.

The Dowlais was tapped at the end of Llantarnam Comprehensive Schools football fields and it was then canalised into its present course today. There could be an argument built for Cistercian management of this water course as far up as the Mill Tavern Public House (where I have we heard that one before?), although I am unsure of this at present and it needs a lot more research.

The Dowlais Brook: Canalised for the transport of materials and to open up the area available for the inner precinct.

Both systems probably fed extensive medieval water meadows which are now, in the main, built on. I’ll have to deal with water meadows at another time but trust me, they were very important to Llantarnams wealth.

There is another system that fed the Dowlais but this one may have entered the Dowlais inside the outer precinct. This water system is smack bang in the middle of the proposed development area. The reason for its existence is open to debate but let me show it to you now so that you can see, and hopefully understand, the problems that our current planners have. There are two leat systems that carry water towards the Dowlais Brook. Think of a leat that is cut in a V shape into the ground. There is a lot more to it than that of course but that explanation will do for now. As I am not allowed onto the land that is proposed to be developed on, the systems are very difficult to photograph, I hope to remedy this soon.

The leat at the top of the picture leads down from Pen-yPark

The lower leat is running behind the tree from the bottom left of the picture to the top right, its source is unknown.

These two leats lead from an unverified source, although there is a very tempting possibility, for at least one of them, that was not identified with Llantarnam, that popped up during GGAT’s watching brief for the relief road for Brynglas tunnels.

It reads,

The substantial remains of a dam were recorded in advance of the construction of the Brynglas Tunnels Relief scheme, financed by the Welsh Office Highways Directorate. This feature crossed the line of the small stream valley leading from Pen-y-Park to the Crindau Pill and measured some 55m in length, 6m wide and 3.2m high. The maximum area of the impounded pond would be 160m by 50m and up to 3m in depth.

It is probable that the dam formed a header pond to a mill, so far unlocated, further down the valley, although no documentary evidence has been found for a mill in this area.

Now what if they looked (thought) the wrong way down ‘a’ hill and didn’t think of the Abbey? Possibly because of the current topographical situation? It is also quite possible, given the size of the dam, that it fed more than one water system. The Cistercians, after all, were complete masters of water management. Lets not underestimate their capabilities here.

The two systems run down towards the Magna Porta gatehouse that sits on the line of the current grade two listed conservation area. As you look at the gatehouse, on the left you will see the remains of a dam.

A similar dam to this one has been discovered during the Strata Florida Research Project. The conclusion, that was arrived through excavation, was that the area behind the dam was ‘a boggy area which other trial excavations have shown to be a possible settling tank for clays‘ (scroll down).

That is not all, where does the water go after being drained from the dam at Llantarnam? It enters the Dowlais brook through a drain. Much hidden, under a dense and large canopy, I eventually found this by accident while trying to fight my way through vegetation that I had not explored before.

It does not look like much to shout home about perhaps? Take another look, this time at the inside, that way you see the construction technique employed.

This system is still in operation. As the catchment area for the two leats is so large, heavy rainfall means that the drain will empty the fields above of any excess water. The water then flows, quite freely, into the Dowlais Brook. It is a pleasure to watch it flow after being built so many years ago. Ok so there are not any Lay Brothers operating the drain that would have released the water, mother nature has taken over, but you get my gist.

This is just one of many micro water systems that fed Llantarnam Abbey. The hydraulic systems are vast and complicated but at the same time, exciting for the study of monastic water systems.

Further, there is an opportunity here to investigate a medieval park, the park, or outer precinct may remain untouched since medieval times; it was in one family (the Morgans and their descendants) for a very long time after the reformation and this fact should not be dismissed without serious investigation. The outer reaches of Llantarnams current park could quite easily derive from the monastic outer precinct.

The planning process employed by the Cwmbran Development Corporation, while destroying vast amounts of the historical landscape, left us with pockets that have the ability for current investigation, the area for the proposed development is one of them.

Think of Cwmbran as a large 5,000 piece archaeological jigsaw. 4,500 pieces of that jigsaw were wiped out when the New Town was built. We have about 200 pieces left on the lowlands, another 200 pieces on the uplands. 50 pieces are left scattered in the middle belt of her lands. Unless we understand the whole picture of this jigsaw we will will be left with an archaeological void, one that can can not be back filled. In a hundred years time, unless this planning department changes its tune, future archaeologists are going to look back and laugh, pointing at our total and utter inability to see a historic landscape that is crying out for serious research using early 21st century archaeological techniques.

Let it not be seen that we never tried to put together the remaining pieces of the jigsaw of this almost impossible puzzle. Are we really going to place the remaining pieces in the recycle bin? Oh well, at least they are collected weekly.

It is not like having the most brilliant Cistercian water systems in your home town is important is it?

Is it?

If you wish to oppose this development then please send an E-Mail to LDP@torfaen.gov.uk It has to arrive in their electronic box by 4:30PM on 6 January 2012 otherwise your comments will not be considered.

MD

As well as social media giving me the opportunity to excavate on rather exciting Scheduled Ancient Monuments, it also gives me the opportunity to follow local councillors who happen to use it. One councillor who fits that billing is Clr Fiona Cross who represents the Coed-Eva ward in Cwmbran. Clr Cross also happens to be on the planning committee for Torfaen and intermittently posts information on planning committee decicions about local developments. This happened at the start of this week, when it was announced that planning permission had been granted for five detached houses on land surrounding a public house called The Mill Tavern, in Coed-Eva.

Naturally I asked for a copy of the archaeological desk top report. There were a few reasons for this: One, the building is on Cistercian lands and it used water management; secondly, as it used to be my local I knew it had some unusual features and three, until recently, the water wheel and wheel pit were still visible. Other interesting features that would have been picked up on were the fact that a tramway from Henllys colliery ran past The Tavern on the way to the brickyards and ultimately the canal. As the tramway ran over the leat for the mill there may have been some sort of structure in place to bridge it. Also, at the back of my mind, I could remember that when I was a young scallywag, there was a rather large pond in one of the gardens about three hundred metres away. I thought it odd that the mill pond should be so far away and wondered if there was a possibility of another mill close by. So, in a nutshell, there could be some very important Industrial archaeology to have a look at, some Post Medieval mills to look at and lastly, the remote possibility that the Post Medieval mills were re-built on top of Medieval structures. Very juicy, and given my local connections, one that I was looking forward to getting my hands on and head in.

There is no archaeological report.

The building is now going to be inspected by one of the planners at Torfaen and if he decides that there is nothing of historical importance attached, they are going to level it. I know how this works around here, trust me, it will be levelled, quickly as well.

So I decided to have a little rummage through some easy to access resources to see what, if anything, cropped up. The first port of call for me is the first edition Ordnance Survey maps circa 1880. As I was at Pontypool Museum today doing some research for an assignment I have to complete, it was the perfect opportunity to have a look in the research library they house there.

The first edition ordnance survey map - 1880

It is quite plain to see that there is not much going on in the area at that time! The sheer size of the mill pond is very impressive. The water, drawn from the Dowlais brook, enters through two sluice gates and after turning the water wheel of the corn mill, the tail race then travels towards The Mill Tavern to mechanise its own overshot wheel. So, we now have a double mill complex on our hands. The tramway, circa 1814, can be clearly seen running across the map from the top left, down past the Mill Inn and then carrying on what is now Two Locks road. The Mill Inn can be seen to have been a singular structure at the time. Just to the north west of the mill another large building, of which none remains today, is present. And just to the south there are a peculiar set of small outbuildings that are sat precariously close to the Dowlais Brook. The remains of these outbuildings can be viewed in the car park of the mill, precisely where they are going to develop. Sadly, I did not have the chance to photograph them today as the light had diminished by the time I spotted them.

The next generation of maps I looked at were of poor quality, so I then jumped to the 1920 editions to see how the area had developed in the following forty years.

ordnance survey map - 1920 edition

As you can see, the corn mill is now marked as disused although the tail race is still in place. To the north of the corn mill a building has appeared which is still there today but just to the north west the building seems to have developed lengthways and in its later days I know this was used as stables. Just a little to the north west again, another building has appeared while the Mill Inn and the large house close by have remained the same. What has changed is the boundary of the Mill Inn, is has been enlarged into what is the car park today.

I decided to visit the site today to what was left of all of these remains. I invited Clr Cross to attend as the site is in the ward she represents and any development affects the people living nearby.

The large mill pond now looks like this.

Oh dear! The mill pond has disappeared

Gone. And not one shred of archaeological evidence was attempted to be retrieved. Well, this is Torfaen. It is a shame that heritage is being systematically destroyed like this. Just because this land is in Torfaen does not mean that the council have the right to destroy it. It doesn’t belong to them, it belongs to the people of this country. I suppose there may be a slight chance that the remains of the sluice gates and edge of the pond are still in place in peoples gardens but are they really going to let people in to dig their gardens up? I have no problems with houses having to be built, but for the love of God, let us investigate them properly beforehand. And I don’t mean one of those botched, rush jobs either you know, just before the foundations are laid.

Next up is the building that appeared in the forty years just to the north of the corn mill.

Developed again since the 1920 map was drawn, it is a fine example of a house built at the turn of the 20th century. It is just after I took this photograph that I spotted the house sitting behind it. Built in stone…

How peculiar, I thought. Windows that appear to go underground. I had never been able to enter here before as it was a farm yard. Wandering onto peoples land is not the done thing but now there was a road way and there were certainly no signs asking people to stay out. So in I went.

Its hard to explain what it is like when you ‘discover’ something for the first time. I tend to smile a lot, which in turn makes people walking past in the street, stare . Not that it worries me, I couldn’t care less.

The wheel shaft was still intact!

The wheel pit complete with water wheel!

Can you imagine how I felt? I have since found out that the machinery inside the cellar is there, but it is in need of renovation. What a find! I had gone from complete and utter despair to one of stupid grin in a matter of seconds. When I start taking photos at times like this, they invariably turn out to be out of focus as my hands can’t quite stay still. These are the ones that I took a bit later on, after I had calmed down a bit.

So all in all, the visit to the library, coupled with the site visit today, has raised some interesting questions.

Was the Mill Inn just a mill prior to it selling beer? If so, when did it develop into an inn? Was it at the time of the tramway being built in 1818? Were the Mill Inn and the corn mill contemporary mills? How old are they, and if they are dated to the Post Medieval period, were they re-built on Cistercian mills? What was the large building to the north of Mill Inn? What remains are there under the car park that is to be re-developed? What are the small out buildings close to the Dowlais, that can quite clearly be seen today? What is left of the tram way under the car park? Was it bridged to go over the mill leat? How big was the mill leat and when was it built? Archaeology could help us solve some of the many questions that can be raised. There are many more. What remains of the mill machinery lies within the Tavern today? The wheel shaft would have entered the cellar and it should be noted that the floor of the original Inn is a lot lower than the road today, another indication of how old it could be.

But alas no, it will not happen. The planning committee were lied to in their meeting, they were told that no archaeology existed under there. This simple piece of research, two historical maps, proves whoever said that was wrong, totally wrong. In fact, it is slightly embarrassing how wrong they were. Who are these people accountable to? They seem to be able to knock down or dig holes where they want, how they want, with no scientific investigation whatsoever.

When Cwmbran new town was built, a lot of old buildings were destroyed with no investigation carried out on them at all. What is done is done but is it really to much to ask for Torfaen to actually look after and protect our heritage, the Welsh peoples heritage?

They should not be allowed to continue this wanton destruction of sites that could hold some important clues for us in understanding this towns past, but they will.

MD

Accept the things to which fate binds you, and love the people with whom fate brings you together, but do so with all your heart.

Marcus Aurelius

Fate. Such a strong word for one so small. As I was finishing another blog post I had no idea that a very timely hit on the Twitter button would lead me to another excavation. There was no way I could have known who was online at the time of publishing, let alone if they would read it, but they did.

The Council for British Archaeology have very generously sponsored CADW to enable them to employ a community archaeological officer. The officer read on my blog that I had enjoyed taking the general public around Caerleon and mentioned that there was an opportunity to do the same at an up and coming community excavation. This had been organised near a Scheduled Ancient Monument called Tinkinswood. I couldn’t refuse. The site is an early Neolithic burial chamber of the Severn Cotswold type and is thought to hold the largest capstone in Britain, weighing in at an impressive forty tonnes.

First excavated in 1914 by John Ward, the keeper of archaeology at the newly built national museum, the burial chamber was found to contain nearly a thousand individual bones. The bones were a variety of ages, of both genders, with about fifty individuals represented. Pottery was also found, although the majority of this was near the entrance of the chamber and has been linked to ceremonial purposes.

That is not the whole story, nearby were other strange features and these were not understood. So an excavation proposal was created and the funding sought. With all of the T’s crossed, the I’s dotted and the go ahead given, we all met up on the 22nd October to investigate these features with the hope of some answers being forthcoming. And they were.

There were three areas that were to be looked at through archaeological investigation. Two of the areas are on the link above, the third was a potential quarry where the huge capstone was thought to have been lifted from. It was in this area that I was to spend the majority of the next two weeks. We had a remit for up to ten test pits as we were charged with looking for any signs that prehistoric quarrying would have left.

So what were we looking for? Hammer stones for one thing, quite literally prehistoric hammers. We were also on the look out for antler picks. Formed from the antler of a red deer, these tools were commonly used by Neolithic communities in north west Europe for the excavation of soil and quarrying out stone and bedrock. If these were present then other finds, such as worked flint and pottery, would help us date when quarrying had been undertaken.

We only managed to open up six test pits for a variety of reasons. The ground was like concrete as the tree roots had naturally sucked up any moisture from the ground that was present. Secondly the roots themselves were in every test pit that was opened up. Some of these were very large and it was time consuming trying to remove them.

Another reason for only opening up six test pits was the fact that were under quite a dense tree canopy. Don’t get me wrong, we had great weather over the two weeks, but the canopy was just too dense for sunshine to penetrate it adequately. When it was overcast it was particularly bad to spot things like soil colour change or even small finds. On one overcast day, I was standing in the quarry area looking out towards where people gathered at the start of the day.

Hopefully this picture will illustrate how bad the conditions could get if the sun didnt shine. I turned my flash off for that picture and you may be surprised to know that there is a test pit in the bottom of the photograph, just to the left of the tree on the right.

Anyway, enough of my griping and moaning, what did we find in the quarry area? The answer to that is, not much evidence of prehistoric quarrying material at all! It has to be said though, my favourite find from the whole excavation popped up out of test pit two. A volunteer had been placed in there and it was hard going due to the reasons given above. As I walked past the pit the volunteer asked me ‘is this anything because if it isn’t, I would like to take it home as it sits so nicely in my hand’! Alarm bells started ringing!

While I was writing my last blog, Roman Plumbing at Isca, I stumbled across something that was relative to an earlier blog regarding excavating at Caerleon. You see, I have found that the port is not first time that tegula walls have been excavated at Caerleon.

Brick that will not stand exposure on roofs can never be strong enough to carry its load in a wall. Hence the strongest built brick walls are those which are constructed out of old roofing tiles.

Marcus Vitruvius Pollio: de Architectura, Book II

Now it starts to make some sense, to me at least, on why there was so much wall construction using ceramic building material (CBM) at Caerleon – quite simply, it was in one of their construction manuals.

Between 1977 and 1981, the Fortress Baths at Isca were excavated by J. David Zienkiewicz. The culmination of his work are two rather large volumes detailing his findings, and the impressive building preserving the excavated baths for the general public to view today. The first stone building within the fortress, it was constructed around 75AD and testament to Roman construction techniques, it was probably still standing in the 13C when it was demolished.

The building that concerns us here is called the natatio. This was an external pool holding some 80,250 gallons of water and measuring 135 feet in length. The shallow end measured 4 feet and this shelved down to 5 feet at the deep end. There was evidence of a fountain house at one end, constructed during the first phase, but this was demolished when the natatio underwent quite radical alterations about fifty years after it was first built.

Artists impression of the Fortress Baths at Caerleon showing the natatio and fountain house

The buildings were huge, colossal even. The vaulted ceilings would have been as high as the abbeys that you can still see today. I think that the wall construction of the natatio is best read as the excavator intended.

Above this course, the wall was faced entirely with the flanges of roofing tegulae. None of these tiles were complete, and all were broken so that into a roughly triangular shape so as to maintain the complete length (generally 65cm) of a single flange on the longest side. The tiles were laid in regular courses, with their flanged edges facing upwards and to the wall face, so that their apices bonded them to the mortar core.

Sound familiar? The broken tiles are exactly the same as the port walls described in my first blog on Caerleon. Interestingly he goes on to say;

The tiles were not wasters, nor could accidentally broken tegulae have preserved so many complete flanges. The exclusive use of tegulae for this submerged walling indicates that the material was considered well-suited for the purpose.

Hence my quote from the de Architectura at the top of the page. None of the tiles bore the Legionary stamp which I find unusual, these were in abundance at this years excavations.

Speaking of which I had a very unusual conversation with a student while in trench four one day. The student explained to me that to find a Legionary stamp of the second Augustan Legion was on their preferences list. Ok, the student was young, incredibly focused but I like to find what I find, not what I want to. Nevertheless, I joined in. I explained that I would prefer to find a stamp of the Legio XX Valeria Victrix. This comment produced a very puzzled face for the student. It confused them. Flustered may be a better a word. An hour or so later we walked back from lunch. I asked if my statement had been talked about by their fellow students, it had, and all of them were in disagreement with what I had said. Asking if they were betting people, something I normally do not succumb to, I was told that they were. Now I had a moral dilemma, do I make a shed load of money by betting them five pounds each that I was right, or do I leave them be? I settled for the latter and I am not flushed with money by any means.

Usk also housed a Legionary Fortress. Unlike Caerleon, it was Pre-Flavian and built C55AD. By C64AD it is assumed that the Fortress was occupied by the XX legion. But the student(s) would not buy this train of thought. The Usk excavations were huge and they really help our understanding of the downfall of the Silures – the Iron Age tribe of the area. Systematically demolished after just 20 years it has been suggested that the timbers from the fort were then floated down the river Usk to be used at Caerleon.

As you have probably realised, there is the connection. The first stone buildings at Caerleon were the Fortress Baths – built using tegulae, the port was built using tegulae, was the port built prior to the baths or are they contemporary in date?

Its a big question, only the dating material for trench one may help us understand that.

I think that is enough of Italian Holiday Camps in Wales for now.

My next blog will be Medieval, back to the Cistercians, perhaps.

MD

“It is to be observed that the pipes take the names of their sizes from the quantity of digits in width of the sheets, before they are bent round: thus, if the sheet be fifty digits wide, before bending into a pipe, it is called a fifty–digit pipe; and so of the rest.”

Marcus Vitruvius Pollio: de Architectura, Book VIII

The word plumber dates from the Roman period, in Latin lead is plumbum; those that worked the lead, the plumbers, were known as the plumbarii and of course the symbol for lead is Pb in the periodic table.

“Dave, you’re in trench six today with Rob, is that ok?”

At first I thought that was a joke for I knew what was in trench six. Quite unashamedly, I wanted a part of it. It had been unearthed some days earlier and Time Team had already been in there so that they could be filmed having a little crack at it. Its how television works. I knew lead pipe had been found at Caerleon before, an eleven metre section had been recovered from the School Field excavations in 1928, but to be part of this one was an amazing, selfish, opportunity.

Funnily enough, even though I knew what had been found I hadn’t had the time to go and actually see it until the night before I ended up in the trench. We had been so busy in trench two that the other trenches had no concern for me. The pipe had been adequately protected by a plastic sheet.

The spur interested me, to see a welded joint from this period that was obviously still in-situ is rare indeed. To have a spur of a smaller bore to the main pipe was even better. When a water system is gravity fed, as this one would have been, there are two ways to increase pressure. The most obvious way is to increase the incline of the pipe so that the water runs through it at a faster pace. The other way of achieving pressure is to tap the main pipe with a smaller bore. The pressure from the larger bore is immediately increased. This is what we appeared to have in this instance. The big question was why? The favourite theory was that it led to, and then, powered a fountain. Well, did you expect anything else?

With the plastic removed, a quick clean of what what was there began to give a better insight into what we had.

So, not only did we have a smaller bore but it appeared to be falling at a steeper angle to its larger supplier, increasing the pressure even more. As you can see (at the bottom of the picture) the pipe had a wall constructed around it and it was the other side of this wall that had to be excavated next to see if the remains of the pipe continued or had it been robbed out in antiquity.

This turned into quite a difficult task. There was not much room to play with, I couldn’t really place my feet on the wall as it had been semi cleaned, rendering the masonry unstable, and the extension to the trench was not at all large for somebody of my height. To top it all off the local media had published that Time Team were going to be present over the Bank Holiday weekend. They weren’t, they had left on the Friday but the hoards of public visitors increased no end. As much as you concentrate on the job in hand, having between 20-50 members of the public standing at the edge of a trench you are working in does slow you up. Its a distraction. Nevertheless, if it was not for the public tours the next picture would not have been possible. Thank you Lynda, you’re a darling.

With your ankles next to your rear end, your knees next to your chest, and having to concentrate on what your trowel reveals, is a tiring exercise. After carefully excavating what was in front of me, I had to turn around and excavate what was behind me – without disturbing what I had just uncovered, or the remains of the wall. My knees went first, the back second but I didn’t tell anyone; determination carried me through. I am glad it did, the pipe did carry on but not as we thought it may have. It had collapsed at some point which meant that it was at a much lower level than expected.

Next up was the cleaning of what you can see in the right hand side of the photograph above. That was going to be at the forefront of the photograph for publication. The key with that is that you carefully remove all of the soil that is around the masonry without disturbing it whatsoever. For sure you will disturb one or two of the smaller stones but by and large they have to be kept intact, removing them would destroy any possible hope you may glean of understanding the construction and/or the collapse of what was there. The majority of this was achieved using a small implement known in archaeological circles as a leaf and square [trowel], they are tiny.

It was the most painstaking but rewarding work I have ever done, The resulting pictures should give you a clue as to how it turned out.

The day after I was sent to another trench. I never did get the opportunity to de-construct the overlying wall, which was a shame. But that’s the thing with a training excavation, there is no ‘I’ in team, other students had to have the opportunity to finish off what I was lucky enough to have started. Before I had even got to trench six there had been a hoard of students and volunteers slaving away in there, for weeks on end. I believe that I was the lucky one to have been able to clean the pipe up. That’s life I guess. Some you win, some you lose.

The pipe was fully excavated by the time the trench was closed down. Take a look.

Next up, lets go back to the CBM and the Legionary Fortress’ of Wales – That will be a big pile of fun.

MD

During the summer of 2010, Cardiff University continued with a large scale excavation within the legionary fortress of Caerleon. This was part of the Priory Field Excavations 2007-2010. While there, as part of their under-graduate degree, the students undertook a huge geophysical survey of the fields to the south of the amphitheatre. This produced quite remarkable results and the resulting interpretation of the survey shows a monumental complex lying next to the river Usk.

Those of you that have visited the amphitheatre at Caerleon will be able to recognise the sheer scale of the construction - It dwarves it in comparison.

This exciting discovery was released to the press in August 2010 as test pits in the area were being excavated. One of the test pits was placed quite close to the river Usk and it threw up a wall built entirely of tegula. These are roof tiles and when used in conjunction with imbrices they formed a durable and waterproof roof covering.

Each tegula (a) overlaps the one below it and its raised lateral borders tapering in to nestle between its lower tile's upper border. Each curved imbrix (b) covers the side ridges of the joints formed between adjacent tegulae. Some imbrices are not shown in order to reveal the details of the tegular joints.

So why on earth were they used during wall construction? Obviously they are waterproof so they would be ideal for a port but the port excavated in Caerleon by Boon in the late 60’s produced walls built entirely out of masonry. A comparable had to be found. Dr Peter Guest found that the port walls in Ostia – Harbour City of Ancient Rome were built of the same Ceramic Building Material (CBM) and armed with this information he approached CADW with a plan for nine evaluation trenches during this summer. The laying out of the trenches was undertaken by Tim Young of Geoarch and he blogged his activities for The Day of Archaeology 2011.

As you can see, most of the trenches were of the same size. Two metres wide and twenty metres long. Only two were different, trench one and trench three. Evaluation trenches are just that, they are there to evaluate what the archaeological remains could be. It is minimum invasion for maximum information. As it was already thought what was known in the area of trench one, permission was granted for a larger area to be evaluated. Trench three had the same area to be excavated as the rest of the trenches, forty square metres, but the shape was different at ten metres by four. After a brief spell in trench five, it was trench one that I ended up in.

The wall had already been re-exposed by the time I got there. The photograph to the right is facing an easterly direction. The right hand side of the photograph is near to the Usk and the test pit excavated in 2010 can be seen at the bottom. As the trench was widened the tegula wall majestically extended across the width of the excavated area. For some reason the Roman engineers had built the wall slightly wider than the width of the actual tile. To do this, each tile was roughly split down the middle and then each course was laid down using clay mortar – thus ensuring a water tight barrier.

One of the first questions that I asked myself was why construct the wall wider than the tiles? The tiles could quite easily have been moulded in a different size. Judging by the scratch marks on the back of each tile the moulds were probably made of timber and as such, easily made or easily altered. That not being the case there must have been another reason why these tiles were used and the answer may lie in the fact that they were mass produced. Is it possible that these tiles were the result of surplus production? It would certainly fit in with the amount of CBM used as walling found in other trenches around the site. If that is correct, how on earth did the Roman military machine, normally so efficient when it comes to construction, allow so much surplus material to be manufactured?

I could probably give umpteen reasons for the use of this material ranging from it being easier to use construction wise, to the tiles being seconds or broken during the manufacturing process. Each theory would be hard to argue against.

That is not the end of this particular story in trench one. On they went, deeper and deeper to try and get a further understanding of the archaeology.

This is the eastern side of trench looking towards the Usk. Interestingly a river cobble foundation was used to support the riverside wall.

Looking from the Usk side at the same wall you may notice a dark staining of soil right next to the wall. This is probably the remains of timber, possible used as part of a jetty projecting out into the Usk. This development would give us a direct parallel to Boons excavation of his third century port lying to the west of the amphitheatre.

All in all this trench was fascinating to watch as it developed over the weeks of excavating. I haven’t revealed all of its secrets, some of which I found quite surprising. Other areas of the trench threw up some quite surprising archaeology, not least because the geophysical survey had not revealed it.

Now that was fun.

MD

I’ve been busy. Ultra busy.

It all kicked off when the Council for British Archaeology launched its Day of Archaeology to take place on 29th of July 2011. It ended up jam packed with 400 archaeologists from all over the world documenting what they did on that particular day. Well, most of them anyway. Some were a little sneaky and just documented what they did as their everyday job. Others, like myself, actually wrote what we did on the day.

I posted an introduction about what I was going to attempt a week or so before the day and this was published online on the 29th. It did not go exactly to plan but as you can see lessons were learned and they will hold me in good stead for the future. So that was that, I enjoyed it, and will certainly do it again if I have the free time to take part next year.

While organising that something else popped up that I just couldn’t leave alone although what I wanted to do and what I actually ended up doing were quite different. As part of The Festival of Archaeology I visited Caerwent’s military base to be shown around by representives from CADW.

It turned out to be an interesting day for a number of reasons. Firstly, the buildings hastily erected during the build up to World War II are quite rapidly disappearing. Apparently, a corps of the British Army know as the SAS require buildings to practise demolition on. Seeing as there were an abundance of these at Caerwent it seemed logical that they could be blown up from time to time. Now it is all well and good blowing these things up (probably for fun) but it means that unless they have been recorded there is not much left after demolition to record. CADW, thankfully, have recognised this and have duly scheduled most of the remaining buildings at Caerwent’s base to save them for future generations. And it has to be said good on them for doing so.

The second reason why Caerwent was interesting is that I happened to meet the president of Cardiff University Archaeological Society. We had already chatted through Twitter about the possibility of me delivering a seminar, centered on Llantarnam Abbey, in the coming year, so to meet face to face was brilliant. The excavations at Caerleon cropped up in conversation and I ended up being introduced to Dr Peter Guest by the side of Trench one the following weekend…

Excavating does not really bother me, I am a non-invasive sorta guy when it comes to archaeological investigation. Saying that, I have trenched many times on various excavations. What interested me at Caerleon was not so much what was being revealed but how the whole thing was run and organised. I volunteered to help on the community archaeological side of things and my offer was duly accepted. Imagine my surprise the following weekend when I ended up in a trench, trowel in hand!

It was thouroughly enjoyable though, the experience of a large scale excavation was gained albeit through the eyes of an excavator. Not only that, I also got to interact with the general public as open days had been organised over the Bank Holiday weekend. I took several groups around the trenches explaining along the way what was thought to be in each one.

Yours truly, addressing the general public at Caerleon

So, what was found? Where exactly did we excavate and why? Not many people realise that there has to be a reason to excavate. You have to have good reason esspecially as this land had been protected for many years.

The answers to those questions deserve a page of their own. Watch this space.

MD

Majid Rahman

Majid Rahman